How to Create a WordPress Settings Page with React

While building some plugins, I figured creating dynamic applications in WordPress Admin is much easier with React components compared to using PHP and jQuery like back in the old days. However, integrating React components with WordPress Admin can be a bit challenging, especially when it comes to styling and accessibility. This led me to create Kubrick UI.

Kubrick UI is a React-based library offering pre-built, customizable components that seamlessly integrate with the WordPress admin area. It improves both visual consistency and accessibility, making it easier for you to create clean, dynamic interfaces in WordPress Admin, such as creating a Custom Settings Pages.

Before we go further, I’d assume that you’re already familiar with how WordPress plugins work. You’re also familiar with JavaScript, React, and how to install Node.js packages with NPM as we won’t dig into these fundamentals in this tutorial. Otherwise, check out our articles below to help you get up to speed.

If you’re ready, we can now get started with our tutorial on how to create our WordPress Settings page.

Project Structure

First, we are going to create and organize the files required:

.

|-- package.json

|-- settings-page.php

|-- src

|-- index.js

|-- App.js

|-- styles.scss

We have the src directory containing the source files, stylesheet, and JavaScript files, which will contain the app components and the styles. We also created settings-page.php, which contains the WordPress plugin header so that we can load our code as a plugin in WordPress. Lastly, we have package.json so we can install some NPM packages.

NPM Packages

Next, we are going to install the @syntatis/kubrick package for our UI components, as well as a few other packages that it depends on and some that we need to build the page: @wordpress/api-fetch, @wordpress/dom-ready, react, and react-dom.

npm i @syntatis/kubrick @wordpress/api-fetch @wordpress/dom-ready react react-dom

And the @wordpress/scripts package as a development dependency, to allow us to compile the source files easily.

npm i @wordpress/scripts -D

Running the Scripts

Within the package.json, we add a couple of custom scripts, as follows:

{

"scripts": {

"build": "wp-scripts build",

"start": "wp-scripts start"

}

}

The build script will allow us to compile the files within the src directory into files that we will load on the Settings Page. During development, we are going to run the start script.

npm run start

After running the script, you should find the compiled files in the build directory:

. |-- index.asset.php |-- index.css |-- index.js

Create the Settings Page

There are several steps we are going to do and tie together to create the Settings Page.

First, we are going to update our settings-page.php file to register our settings page in WordPress, and register the settings and the options for the page.

add_action('admin_menu', 'add_submenu');

function add_submenu() {

add_submenu_page(

'options-general.php', // Parent slug.

'Kubrick Settings',

'Kubrick',

'manage_options',

'kubrick-setting',

function () {

?>

<div class="wrap">

<h1><?php echo esc_html(get_admin_page_title()); ?></h1>

<div id="kubrick-settings"></div>

<noscript>

<p>

<?php esc_html_e('This settings page requires JavaScript to be enabled in your browser. Please enable JavaScript and reload the page.', 'settings-page-example'); ?>

</p>

</noscript>

</div>

<?php

},

);

}

function register_settings() {

register_setting( 'kubrick_option_group', 'admin_footer_text', [

'type' => 'string',

'sanitize_callback' => 'sanitize_text_field',

'default' => 'footer text',

'show_in_rest' => true,

] );

}

add_action('admin_init', 'register_settings');

add_action('rest_api_init', 'register_settings');

Here, we are adding a submenu page under the Settings menu in WordPress Admin. We also register the settings and options for the page. The register_setting function is used to register the setting, and the show_in_rest parameter is set to true, which is important to make the setting and the option available in the WordPress /wp/v2/settings REST API.

The next thing we are going to do is enqueue the stylesheet and JavaScript files that we have compiled in the build directory. We are going to do this by adding an action hook to the admin_enqueue_scripts action.

add_action('admin_enqueue_scripts', function () {

$assets = include plugin_dir_path(__FILE__) . 'build/index.asset.php';

wp_enqueue_script(

'kubrick-setting',

plugin_dir_url(__FILE__) . 'build/index.js',

$assets['dependencies'],

$assets['version'],

true

);

wp_enqueue_style(

'kubrick-setting',

plugin_dir_url(__FILE__) . 'build/index.css',

[],

$assets['version']

);

});

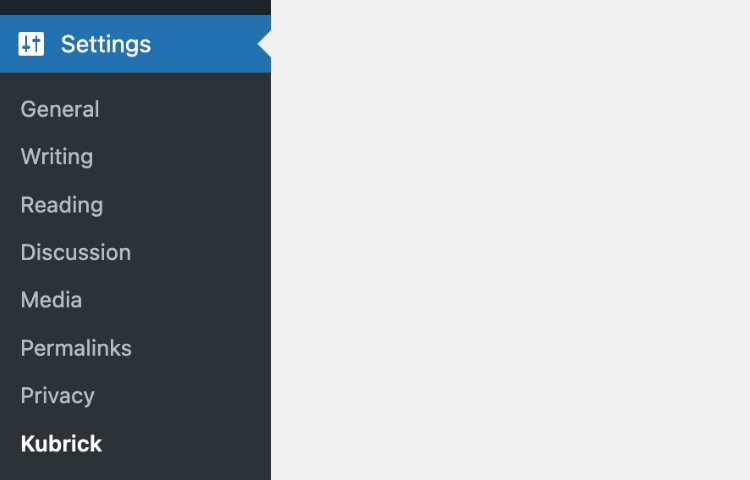

If you load WordPress Admin, you should now see the new submenu under Settings. On the page of this submenu, we render a div with the ID root where we are going to render our React application.

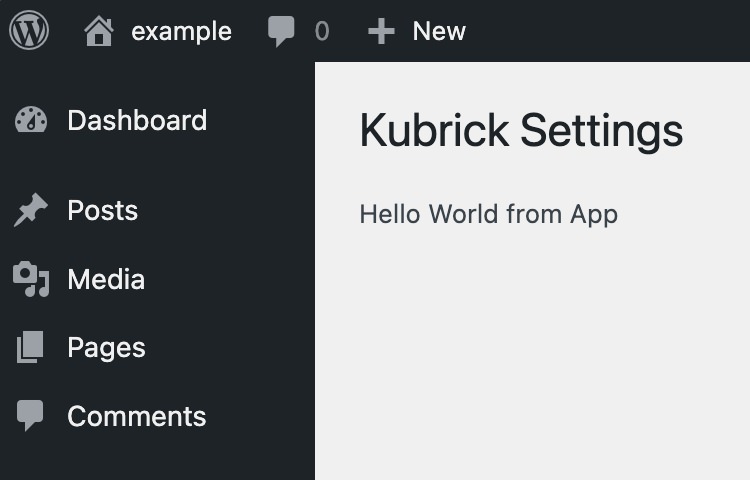

At this point, there’s nothing to see on the page just yet. We will need to create a React component and render it on the page.

Creating a React component

To create the React application, we first add the App function component in our App.js file. We also import the index.css from the @syntatis/kubrick package within this file to apply the basic styles to some of the components.

import '@syntatis/kubrick/dist/index.css';

export const App = () => {

return <p>Hello World from App</p>;

};

In the index.js, we load and render our App component with React.

import domReady from '@wordpress/dom-ready';

import { createRoot } from 'react-dom/client';

import { App } from './App';

domReady( () => {

const container = document.querySelector( '#root' );

if ( container ) {

createRoot( container ).render( <App /> );

}

} );

Using the UI components

In this example, we’d like to add a text input on the Settings Page which will allow the user to set the text that will be displayed in the admin footer.

Kubrick UI currently offers around 18 components. To create the example mentioned, we can use the TextField component to create an input field for the “Admin Footer Text” setting, allowing users to modify the text displayed in the WordPress admin footer. The Button component is used to submit the form and save the settings. We also use the Notice component to show feedback to the user, such as when the settings are successfully saved or if an error occurs during the process. The code fetches the current settings on page load and updates them via an API call when the form is submitted.

import { useEffect, useState } from 'react';

import apiFetch from '@wordpress/api-fetch';

import { Button, TextField, Notice } from '@syntatis/kubrick';

import '@syntatis/kubrick/dist/index.css';

export const App = () => {

const [status, setStatus] = useState(null);

const [statusMessage, setStatusMessage] = useState(null);

const [values, setValues] = useState();

// Load the initial settings when the component mounts.

useEffect(() => {

apiFetch({ path: '/wp/v2/settings' })

.then((data) => {

setValues({

admin_footer_text: data?.admin_footer_text,

});

})

.catch((error) => {

setStatus('error');

setStatusMessage('An error occurred. Please try to reload the page.');

console.error(error);

});

}, []);

// Handle the form submission.

const handleSubmit = (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

const data = new FormData(e.target);

apiFetch({

path: '/wp/v2/settings',

method: 'POST',

data: {

admin_footer_text: data.get('admin_footer_text'),

},

})

.then((data) => {

setStatus('success');

setStatusMessage('Settings saved.');

setValues(data);

})

.catch((error) => {

setStatus('error');

setStatusMessage('An error occurred. Please try again.');

console.error(error);

});

};

if (!values) {

return;

}

return (

<>

{status && <Notice level={status} isDismissable onDismiss={() => setStatus(null)}>{statusMessage}</Notice>}

<form method="POST" onSubmit={handleSubmit}>

<table className="form-table" role="presentation">

<tbody>

<tr>

<th scope="row">

<label

htmlFor="admin-footer-text"

id="admin-footer-text-label"

>

Admin Footer Text

</label>

</th>

<td>

<TextField

aria-labelledby="admin-footer-text-label"

id="admin-footer-text"

className="regular-text"

defaultValue={values?.admin_footer_text}

name="admin_footer_text"

description="This text will be displayed in the admin footer."

/>

</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>

<Button type="submit">Save Settings</Button>

</form>

</>

);

};

export default App;

Conclusion

We’ve just created a simple custom settings page in WordPress using React components and the Kubrick UI library.

Our Settings Page here is not perfect, and there are still many things we could improve. For example, we could add more components to make the page more accessible or add more features to make the page more user-friendly. We could also add more error handling or add more feedback to the user when the settings are saved. Since we’re working with React, you can also make the page more interactive and visually appealing.

I hope this tutorial helps you get started with creating a custom settings page in WordPress using React components. You can find the source code for this tutorial on GitHub, and feel free to use it as a starting point for your own projects.

The post How to Create a WordPress Settings Page with React appeared first on Hongkiat.